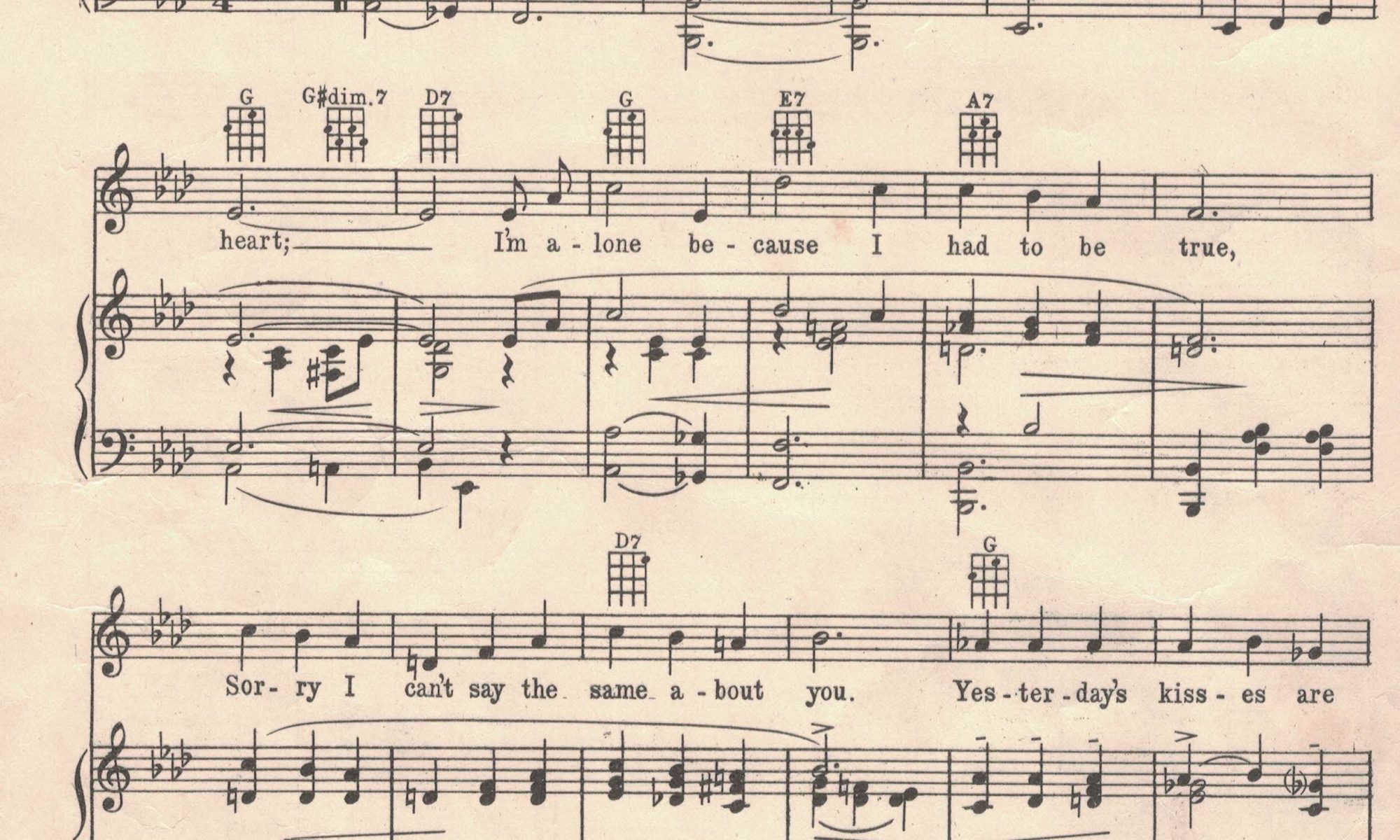

I’m alone because I love you,

Love you with all my heart;

I’m alone because I had to be true,

Sorry I can’t say the same about you.

–Words and music by Joe Young

Before

He was used to girls saying no at first. It meant nothing; it was what they were all taught to do before they said yes. He wouldn’t have expected any decently bred girl to give in on the first try. Even a slut like Kitty from Kansas City knew to hold out until a fella had sweetened the pot a bit. The hotter the pursuit, the sweeter the kisses he’d always said. Besides, this one had come to the party with another fellow. It ruined the optics if she flirted with him right away. So when the brunette seated across from him averted her gaze and withdrew her foot as soon as he reached his under the table for an exploratory nudge, he’d applauded her restraint.

Good girl, he tried to telegraph with a meaningful glance that failed to hit its blushing target. She kept her eyes lowered, examining her salad fork as though she’d never seen anything so fascinating in her whole life. And who knows? Maybe she hadn’t. She was no silver-spoon debutante, for sure. The shiny elbows of her date’s threadbare dinner jacket belied a life of dances and dinner parties. Most likely she was one of those sincere, poetry-loving girls whose mothers scrimped and saved to send them to college in search of a husband. She’d be a lovelorn schoolteacher in no time without his romantic intervention. He knew the type. He was a hit with the mothers too.

He’d simply have to get her alone later tonight. When her fellow excused himself for an after-dinner smoke on the balcony with the boys, when his own date ran off to powder her nose and giggle with her girlfriends, he’d find her examining dusty spines in the corner of the library or gazing dreamily out of the rain streaked window, waiting to be found. He’d surprise her, grab her around that slim waist and pull her close, inhale the perfumed down of her neck. He’d done it a thousand times, with innumerable co-eds; he could already feel the tension in the curve of her back, the curl escaping its comb to tickle his cheek, the crisp intake of air and delightful little shudder of her body against his as he leaned in to do what he did best: croon.

After

The only warning of his approach before she was seized from behind, Madeline realized later, had been the sudden, sharp smell of pomade, which only became more overwhelming as the man spun her around to face him, bending her into an impromptu dip. She pinwheeled her arms in panic, the pomade smell mingled with whiskey as he righted her, closing in for the kiss. She wrenched her head to the side and his teeth grazed her jawline. A spasm of revulsion shook her as he laughed and started whisper-singing that Vagabond Lover song into her ear, his breath hot and moist and reeking. Even then she still had trouble placing her assailant.

No, it wasn’t until she’d wriggled out of his grasp and kicked him between the legs hard, so hard that her slipper was wrenched from her foot and flew across the foyer, nearly missing a large Chinese vase and coming to rest on a walnut side table, it wasn’t until he doubled over, gasping, reaching to steady himself with great effort against the velvet-flocked wallpaper, it wasn’t until she’d retrieved her shoe and taken one last look at him, vomiting miserably into a potted palm as she slipped out the door with neither her coat nor her date, that she placed him.

It was that glee club fellow. She couldn’t recall his name: the one who seemed to materialize at every college function, surrounded by hopeful co-eds. He was always singing songs about spooning with the aid of a megaphone (his voice wasn’t even very good) when he wasn’t cavorting manfully about with his fraternity brothers, roughhousing and posing for the hangers-on who adored that sort of thing. Madeline had never paid his antics much mind, and she hadn’t recognized him without his signature megaphone, not even when he was seated across from her at dinner, playing footsie (she shuddered to recall it now) as his date chatted obliviously with the man to her right.

Madeline quickened her step as a light, chilly rain began to fall. She owed Horace an apology for leaving so suddenly, but she couldn’t imagine explaining what had just happened. He’d want to fight the glee club bastard or make some ridiculous gesture to defend her. She’d make up some excuse when she talked to him later; she had no interest in reliving the scene and even less interest in any sort of romantic display from Horace. She wasn’t much of a partygoer anyway, she’d gone along as a favor to Horace and now she’d embarrassed him by running off.

As soon as she got back to the boardinghouse she would run a bath. She crossed her arms against the cold and pictured it as she pressed homeward: the rising steam, a rough white towel and cake of Ivory soap, water lapping at the lip of the tub, just waiting for her to step in.

After, also

It was his date, Betty Co-ed, fresh from the powder room, who’d discovered him hunched and wretching into the hallway planter, Betty who produced a handkerchief soaked in her signature floral scent to dab the corners of his sour and gaping mouth. And he was grateful to Betty; he appreciated her discretion in not asking why food poisoning would cause a fellow to limp and raise the pitch of his voice. Instead she had sprung into action as efficiently as a general, made excuses to their hostess Peggy and hailed a cab to take him back to the fraternity house where she ministered to him with barely-contained zeal. Gals loved that sort of thing; she was no doubt acting out some Florence Nightingale fantasy as she profferred cold compresses and hot tea laced with brandy and pulled the Pendleton blanket up to his quivering chin.

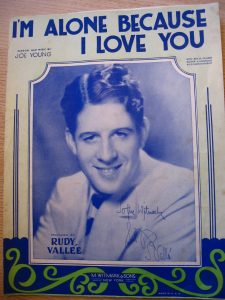

Yes, Betty was a real brick, and he was going to have an even harder time cutting her loose now. Already she was sketching their initials in that little notebook she carried everywhere with her, soon she’d probably start embroidering his name all over her damned trousseau. It had been a mistake, meeting her mother so soon, but Rudy couldn’t help himself–mothers adored him. He was exactly the type of fellow they sent their daughters to college to meet. Kitty from Kansas City’s mother had practically offered herself up in Kitty’s place–the apple hadn’t fallen far from the tree there–placing a fleshy manicured hand on his flannels under the guise of gauging the weave of the fabric, she was a seamstress after all, the shameless old gal.

But as sought after as Betty was (the girl adored from Yale to old Purdue), he couldn’t stop thinking of that little brunette minx who’d kicked him at the party. It wasn’t the kick that pained him as much, he reflected, as the fact that she seemed to mean it, even as he crooned in that breathy voice that had caused innumerable other knees to weaken. Girls who heard him croon always clamored to spoon with him; he couldn’t figure what had made this one so tense. She’d been surprisingly strong; she’d fought him like a bearcat, and somehow this memory had him all inflamed. He felt a new song coming on.

I’m alone, he whispered, because I…

“No, darling,” murmured Betty, stroking his burning forehead, “you’re delirious. Try to get some sleep, I’m right here.”

He felt the lyrics washing over him in waves. If he could only get Betty to leave him for a moment, he could work them out. He didn’t want her to think the song was for her.

“Could you bring me some water?” he asked, and she sprang to comply. There were things about old Betty that he would miss, he had to admit. But she wasn’t the muse he needed.

Yesterday’s kisses are bringing me pain. Yesterday’s sunshine has turned into…

A smattering of raindrops hit the window as if on cue. He’d never felt more inspired. It’d be a real romantic barnstormer of a song, his best ever! A girl like that saucy brunette needed to be courted and drawn out, he realized. Persistence is a virtue; she was testing him. He would find out her name, where she lived, her favorite flower. He would bribe one of her boarding house roommates to point out which window was hers so he could station himself outside. And this time he’d bring his megaphone.

Later still

A sudden illness had overtaken her, Madeline explained to Peggy the next morning when she returned to retrieve her coat and umbrella. She peered past the doorway, half-expecting to see her assailant still languishing on the black and white tiles like a fallen chess piece, but there was no evidence of the previous night’s skirmish. She might as well have dreamt it.

“Oh!” cried her hostess, worried now that the crab hors d’oeuvres that had seemed such a hit last night were perhaps not as fresh as the fishmonger had claimed, “Not you too! That’s why Rudy had to leave!”

Rudy. That was his name. Madeline was tempted for a moment to confide in Peggy, but she decided against it. Mostly she just wanted to go home and forget the whole thing. It wasn’t likely, after all, that she would see him again.